1. Choosing “Invisible” as a UX Feature – Why We Design for Local-Only Access

In the off-grid case studies we publish, our systems are designed so that only local users at the customer site can access the UX. Screens are available over the on-premises LAN or via dedicated terminals; there is no public Internet endpoint, and no smartphone app talking to a cloud dashboard.

At the same time, the system provider – our own operations team – maintains 24/7 monitoring under a clearly defined responsibility framework. In other words, we separate who can observe the system from who is accountable for it.

The goal is not to showcase new technology, but to design something that can be operated realistically for ten-plus years at a predictable cost. From that perspective, a local-only UX is a deliberate design choice, not a compromise.

2. Why a Local-Only UX Is Often the Rational Choice

Many energy, facility and IoT systems today follow a familiar pattern:

- Collect data locally,

- Send it over HTTP/HTTPS to a cloud or external server,

- Render it as a web dashboard or mobile app UX.

On the surface this looks attractive. “You can see it from anywhere.” “Just open the app.” But from a long-term operations perspective, this architecture is high-cost and high-risk.

Even if the UX is “read-only”, the moment you maintain a live communication path and an authentication layer, the system becomes a target. In fact, because it is perceived as “only monitoring, no control”, it is often given lower priority in security planning – which is precisely what makes it dangerous.

3. The Real Risks Behind “Local → Server → UX”

A system that streams data from local devices to the cloud and back into an app inevitably brings in the following components:

- Persistent outbound connections from the customer network,

- API keys and credentials that must be stored and rotated securely,

- Vulnerabilities in middleware, libraries and platforms on the server side,

- Continuous patching of OS, frameworks and runtime environments,

- Legal responsibility for how logs and data are stored and processed,

- Monitoring and incident response for unexpected access or misuse.

These are not one-off costs. They are ongoing operational expenses and liabilities that persist for as long as the service is offered, regardless of how often the UX is used.

A “read-only, no control” dashboard is still part of the attack surface. And because it is easy to underestimate its impact, it often becomes the weakest link in the entire system.

4. Why the Assumptions from 30 Years Ago No Longer Hold

In the past, remote access to equipment was built on assumptions like:

- VPNs over leased lines or fixed IP connections,

- A network administrator who understood the entire topology,

- Accessing parties and responsible parties being almost identical.

Today those assumptions are gone. Carrier-grade NAT, mobile-first connectivity, zero-trust security models, and OS-level sandboxing on endpoints have reshaped the landscape. Simply “being connected” now carries cost and responsibility.

UX, however, has continued to move in the opposite direction: everything is expected to be instantly visible via an app. The asymmetry between UX expectations and what it takes to operate safely will surface as an increasing number of services shut down, servers are decommissioned and apps are quietly discontinued.

5. UX Is Not the Same as “Always Visible”

In our systems, screens are rarely opened during normal operation. In fact,

The more “non-stop” the operation is, the less often you need to look at the screen.

Yet the ability to check it immediately when you want to – that is what creates peace of mind.

From this perspective, UX is not about “always on display”. It is also about not demanding attention when it is not needed.

For energy and infrastructure systems, the best UX is not flashy visualization. It is the ordinary, uneventful day where nothing stops, nothing glitches and nobody has to think about the system at all.

6. The Other Case Study Behind This Design Choice

6-1. When “Connecting Everything” Was National Policy

In the early 2000s, Japan’s national strategy centered on broadband and “ubiquitous” networking. Under the u-Japan policy, the government aimed for a society where everyone and everything was always connected – a direct ancestor of today’s IoT and smart-home narratives.

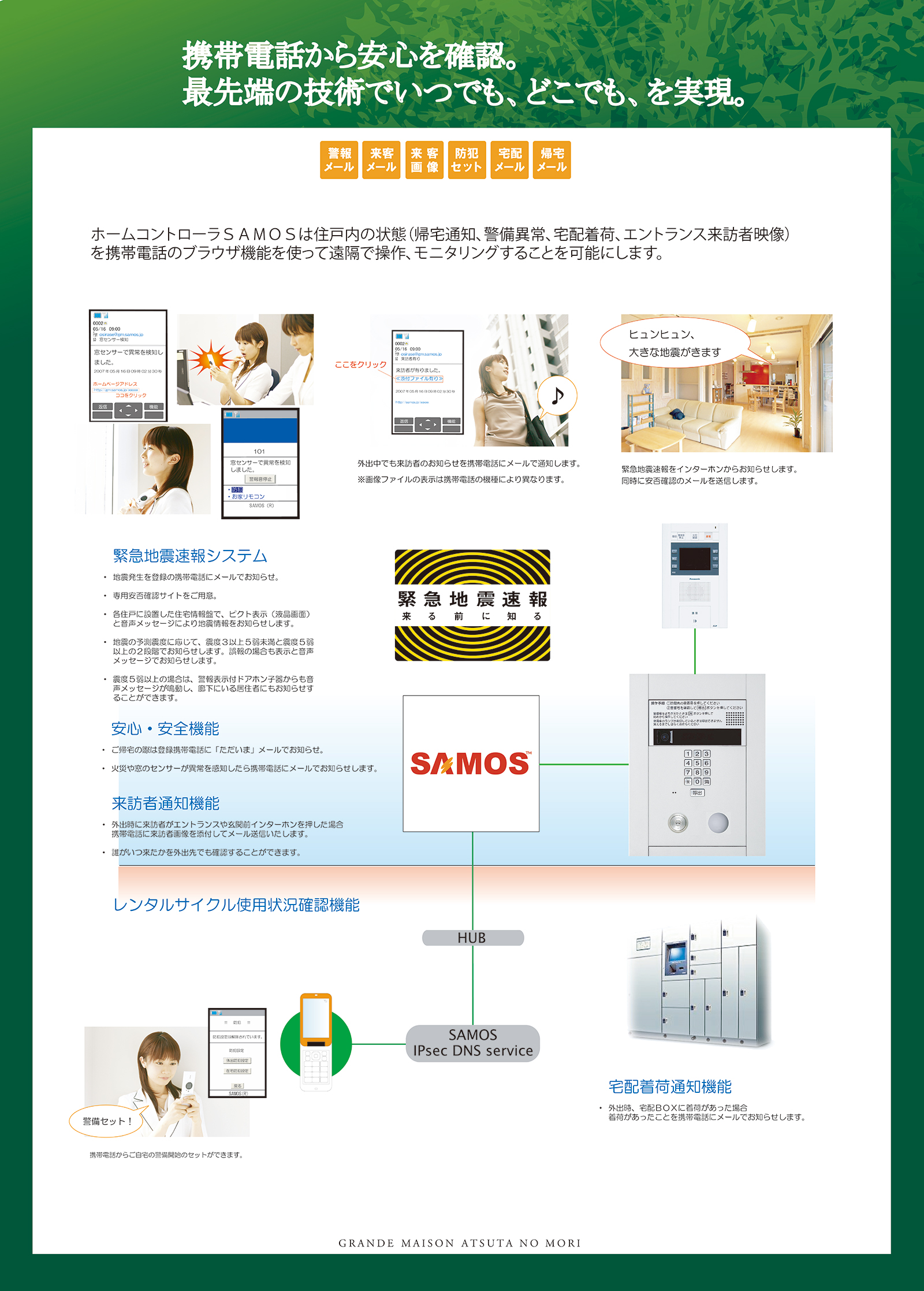

In 2006, our company was selected as a u-Japan “Best Practice” case for a service called SAMOS, a home controller that:

- Allowed feature phones (so-called “Galapagos phones”) to

- Monitor and control home appliances and sensors remotely,

- With no monthly subscription fee and no vendor lock-in.

At its peak, SAMOS was deployed to roughly 20,000 new houses per year – effectively a full-scale smart-home platform long before that term went mainstream.

6-2. Why It Was Secure in the Feature-Phone Era

SAMOS remained safe not because the software was simple, but because of the unique characteristics of feature phones at that time:

- Devices were tightly bound to the cellular network as hardware,

- Each phone had a hardware-level device ID that could not be cloned,

- No software-emulated identifiers could impersonate a physical handset.

We used this device ID as the core of our authentication model, combined with user-side electronic credentials. In modern terms, it functioned as a very strong form of two-factor authentication tied to a non-replicable physical token.

As long as this assumption held, connecting homes over the network was both reasonable and secure. Remote monitoring and control were technically and operationally sound choices.

7. The Turning Point: Smartphones – and the Decision to Exit

This entire security model collapsed with the arrival of the iPhone and modern smartphones. Within a few years, the primary user device shifted from feature phones to app-centric smartphones – along with Facebook, YouTube, app stores and the rest of today’s mobile ecosystem.

Smartphones introduced:

- Per-app sandboxes and opaque OS-level behavior,

- Frequent OS updates that could change network and security semantics,

- Software-based identifiers that can be virtualized and cloned.

In this world, the idea that “device ID = physical identity” no longer holds. The authentication model that had underpinned SAMOS from day one became invalid.

We explored alternative schemes, but they all shared the same issues:

- A single compromised credential could be catastrophic,

- Operational burden and risk would be pushed onto end users,

- Security maintenance costs would grow without bound.

Our conclusion was simple and harsh: continuing the service responsibly was no longer possible. In 2016, despite having a profitable and growing business, we chose to fully withdraw from SAMOS.

This was not a sentimental decision. It was based on the uncomfortable realization that we could already see the future: if we continued, we would eventually face either a major incident or an unsustainable burden on our users. Once that future became clear, “not connecting” was the only honest choice left.

8. How That Experience Shapes Today’s Off-Grid Design

Our current architecture is built on three very simple principles:

- The UX is local-only and completes on-premises,

- There is no public endpoint for the system on the Internet,

- Only clearly responsible parties have monitoring access.

This is not a step backward. It is the logical outcome of having been early in connecting everything, and early in deciding when not to connect.

In the off-grid deployments discussed in our case studies, responsibilities are split as follows:

On the customer side

- Access is possible only from the local environment,

- No permanent external connectivity is required,

- Security updates and operational burden are kept to a minimum.

On the provider side (our company)

- 24/7 monitoring under clear contractual responsibility,

- External access only where we can assume full accountability,

- Integrated design, operation and maintenance by a single owner.

Instead of “anyone can view it from anywhere”, we design for “only those who can take responsibility may view it”. For off-grid energy infrastructure, this is often the cheapest, safest and most sustainable choice.

9. Summary – Prefer “Responsible Design” Over “Convenient-Looking UX”

The key points from this article can be summarized as follows:

- A “local → server → UX” architecture is costly and risky when viewed over a 10-year horizon.

- Unlike 30 years ago, simply being connected now carries significant cost and responsibility.

- Good UX for infrastructure is not “always visible” but “silent when nothing is wrong”.

- Our early smart-home experience under the u-Japan program directly informed our decision to exit that model.

- A local-only UX with clearly defined responsibility can be the most affordable and robust option for off-grid systems.

Off-grid and distributed energy are not just about new hardware. They raise a deeper design question: where do we draw the line between what we control ourselves and what we hand over to external systems? Having experienced both ends of the spectrum, we now choose to build UX that completes within the domain where we can truly take responsibility.